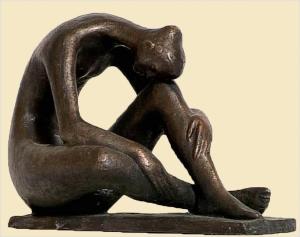

Nancy, after being diagnosed with Stage IV Cancer, leaning up against daughter Maia in 2013, less than a year before she died.

Nancy, after being diagnosed with Stage IV Cancer, leaning up against daughter Maia in 2013, less than a year before she died.

**This blog was written within a year of Nancy’s death, but I wasn’t ready to finish it until just now.

You didn’t want to die. No one really wants to die, do they? I’ve heard of 94 year olds who went out kicking and screaming, certain that it wasn’t yet their time, begging for one more chemo treatment, more time, more life. You were 59, not quite young enough to be considered truly tragic, but not quite old enough to say: okay, she’s lived her life, fulfilled her mission. You left behind two teenaged daughters and a widow whose despair at losing you would inhabit her days for months and years to come. Not quite time for me to be a widow, I say, although at 61 it wasn’t exactly shocking to lose a spouse. Two adolescents who looked around at all the friends they knew who had two living parents. Even those with divorced parents who hate each other still have two living parents. And those with a parent who has vanished from the scene know that they inhabit the earth, somewhere, somehow. Some day that missing parent might be found. I’m not sure which is worse, the potential of a parent being found who has vanished, or one who has vanished permanently. There is no hope of being found.

But, no, you really didn’t want to die—in part, because you knew how terribly we would miss you; in part, because you couldn’t bear to think that you would no longer be a part of our lives. You couldn’t imagine not seeing the hallmarks of our daughter’s progress through adulthood: graduations, first jobs, maybe even weddings and grandchildren. You couldn’t imagine not going to the garden shop with Linda first thing in the spring looking for something new to plant or watching for the lilacs to magically appear after a miserable Michigan winter. Perhaps you wondered what it would feel like not to have me by your side, holding you and sharing the stories of our lives together. You suffered unbelievable agony thinking that you might not see the ocean of Cape Cod once more, where you spent every summer of your childhood and where your brother and his wife and children now reside. You wondered at not only how you would bear to lose your closest family but your dearest friends, who surrounded your bedside with heartfelt vigilance during your last days.

You relished the beauty of this world: sunsets, moving water, grass, plants, and animals. I brought you home from the hospital one summer afternoon, and—sick as you were—the first thing you did was to lie down in the grass, staring out at the blue sky and sun. Some days I would find you sitting in the winter in the outside yard, with your hat and coat on, just sitting, wanting to feel whatever dim glimmer of sun might be found on a winter day in Michigan. You wanted to be in and of this world.

You lashed out at me at the end. How could I be sitting in your hospital room with a Starbucks cup of coffee in my hand, fortunate enough to be able to leave the room, walk through the hospital, and even outside of its doors to fortify my need for expensive coffee? When, finally, you asked me if you were really dying, about three days prior to your actual death and I said, “yes,” you said, “Thanks for sharing that with me!” with sarcasm unexpected from someone who was dying. And, yet, you also listened to my cough as you lay there, and in your most urgent dying breath said, “Go to the doctor!” And in between the grumbles and complaints, there were murmurs of “I love you,” as I moved in and out of caring for you in your last weeks of life.

When we got you home to hospice, I could finally lay by your side. The morphine had ensured that no bones would hurt as I cuddled next to you. We held hands, and I felt your grip, warm and firm. Hey, I’ll take what I can get. We had only a week in hospice at home, hardly time to come to grips with what was happening, at what we were losing, before you slipped into unconsciousness.

And there was the time—maybe a month before you died—when we confessed how happy we had been to have found each other; how each one of us had worried that we might live without love. How fortunate we were to have made a home for ourselves and our children. We had those moments. But not enough of them.

I’ve come to terms with your anger after 3 ½ years. You were given the short end of the stick, while I was given the gift of life, even when it didn’t feel like a gift at times. But still, when I catch sight of a shimmer of peachy sun against the background of our luminescent Michigan winters, I can sense the longing that you must have felt as you said goodbye to the earthly world.